By Rakashi Chand

On this date a century ago, two sailors stationed in Boston went to the sickbay with flu-like symptoms; the next day eight more, the following day 58 more, and this was just the beginning. As we make plans for flu season this autumn, we should remember that this year marks the centennial of the deadliest epidemic of Influenza in modern history. The 1918-1919 influenza, or “Spanish flu,” pandemic killed upwards of fifty million people worldwide and five thousand people in Boston alone, numbers only surpassed by Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. The shocking morbidity pattern killed young, healthy people between 20-40 years of age at an alarming rate, with a rapid disease progression that could lead to multi-organ failure and death within twenty-four hours. The influenza strain was highly contagious and unfortunately spread at exponential rates. Although the origin of the outbreak is still debated, the Spanish media were the first to openly cover the outbreak because they were neutral in WWI. In part because of the war, the U.S. and non-Spanish European press were slow to report accurate information about the epidemic, and the high rate of casualties among military and civilian populations. Some lawmakers also suppressed coverage in an effort to reduce panic.

At Camp Devens, an army training base for 45,000 soldiers just outside of Boston, the first soldier to come down with the flu was misdiagnosed with meningitis and influenza began spreading rapidly throughout the entire camp. At the height of the crisis, 1,543 soldiers were reported ill on a single day. A poignant letter by Physician N. Roy Grist stationed at Camp Devens describes the scene in detail and can be read online: www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/influenza-letter/.

The epidemic soon spread to the civilian population of Boston.

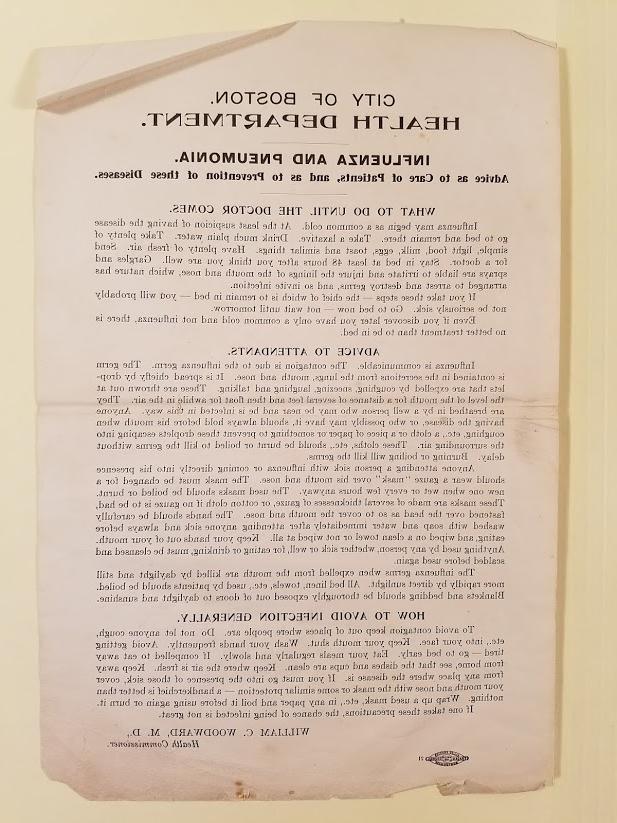

The MHS has a public notice issued by the city for the care and prevention of Influenza. This broadside is an example of the advice given to the people of Boston during the Influenza outbreak by William C. Woodward, the Health Commissioner of Boston from 1918 -1922.

The epidemic took over the lives of all Bostonians. In mid-September, the Boston Globe reported on that the city planned to keep schools open, saying:

Neither Dr. William H. Devine, medical director of the schools, nor Dr. W. C. Woodward, City Health Commissioner, is in favor of closing Boston schools. They say that by remaining at their studies pupils are less likely to become affected, especially since teachers, school physicians and nurses are doing everything in their power to head off the epidemic.

But things turned for the worse very quickly, and people started to panic. No one understood why the disease was spreading so quickly or how to prevent it. Officials in Boston began forbidding public gatherings as they were desperate to try to control the spread of the disease. Finally, the schools were closed, as well as theatres, bars, and even churches were asked to hold not services. City hospitals were flooded with patients, there was an urgent need for doctors and nurses especially since so many were oversees helping the War effort, and, sadly, even coffins could not be supplied at the rate they were needed.

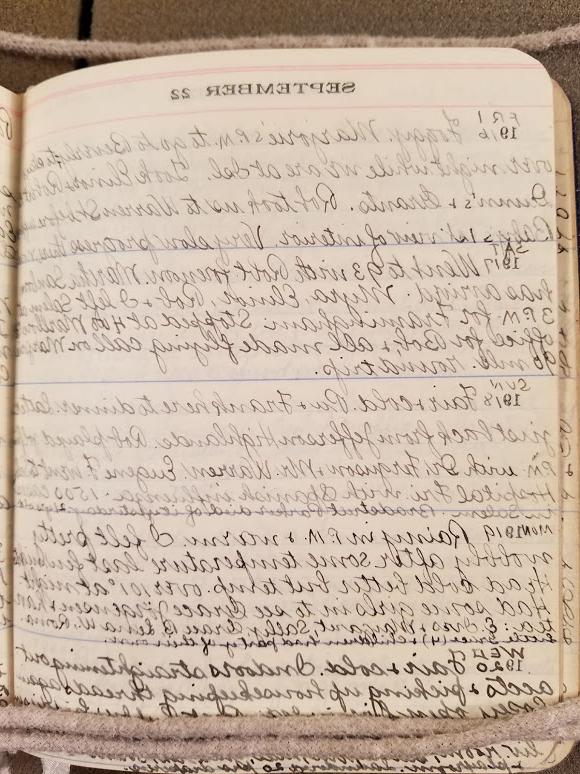

The diaries of Edith Coffin (Colby) Mahoney, from the Colby-Mahoney Family Papers, provide a glimpse of life in Massachusetts during the Influenza Outbreak. The diary Edith keeps is full of descriptions of lovely Golf outings at the Club, picnics, shopping, and friends’ visits during the final days of August, and into September of 1918. But then her daily entries suddenly mention Influenza, and with it, death.

September 22 1918

“Fair & cold. Pa and Frank here to dinner just back from Jefferson Highlands. Rob played golf with Dr. Ferguson and Mr. Warren. Eugene F. went to the hospital Fri. with Spanish influenza. 1500 cases in Salem. Bradstreet Parker died of it yesterday. 21 yrs old.”

September 24 1918

“Mr. Freeman here. Eugene has developed pneumonia from Spanish Influenza. Serious epidemic everywhere. Caned carrots. Went to 93 with children P.M. Myra and Ella go to Gray’s Inn tomorrow.”

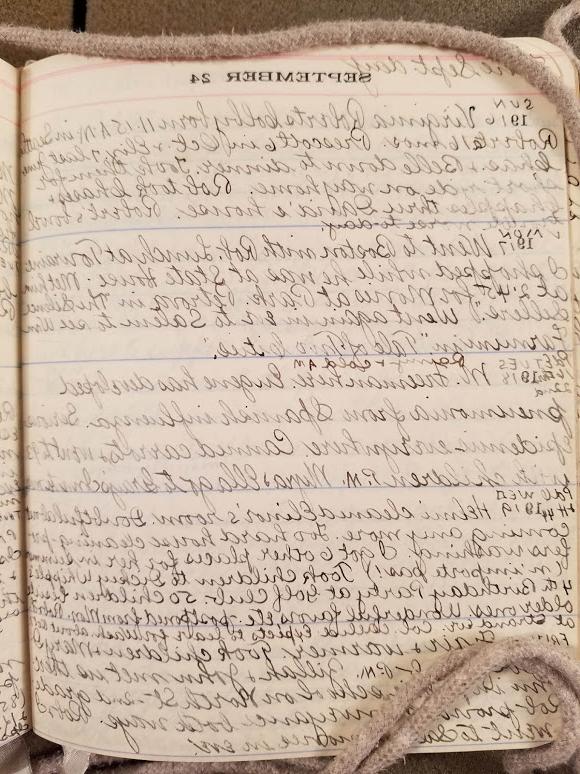

September 26 1918

“Torrential rain for 24 hours beginning at 3am today, some thunder in the P.M.. Most depressing day after bad news from Eugene. He died at 6:40am. Several thousand cases in the city with a great shortage of nurses and doctors. Theatres, churches, gatherings of everykind stopped. Even 4th Liberty Loan drivers parade postponed.”

September 27 1918

“Fair part of day but cold. Had Elwood Noyes get boiler ready and start furnace fire. Out with kiddies in P.M. Called at Ma’s. Belle there with a hoarse cold. Pa here right from office the past three days. Harry at Nasson School to see Agnes who has influenza. Rob home from N. Y. at midnight. Came instead of tomorrow accnt of Eugene’s funeral.”

September 28, 1918

“Beautiful, mild day. Rob in bed all day with high fever, bound up head and aching eye balls, so could not be pall bearer at Eugene’s funeral at grace Church. Prompt measures with hot lemonade, castor oil, aspirin etc.induced god sweat by afternoon so he felt much better in evening. Phoned but did not call Dr. Sargent”

September 29, 1918

“Beautiful, mild day. Rob very much better. Husky throat the only symptom left. Up at noon. Dr. Sargent said to keep him in tomorrow. Met him as I was going to 93 with children in the P.M.. James Tierney died Fri of pneumonia (37yrs). Dr says there is no sign of epidemic abating.”

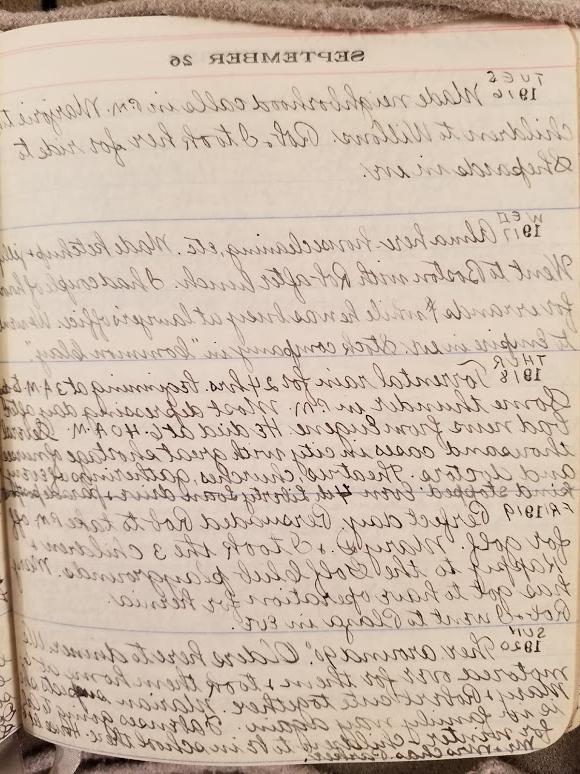

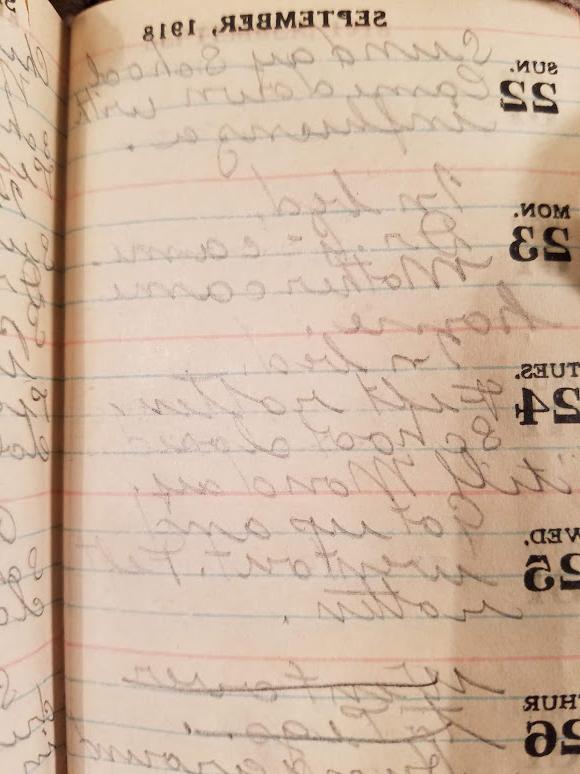

The MHS houses another diary kept by young Barbara Hillard Smith of Newton, MA, describing her experience during the Influenza epidemic.

September 21, 1918

“Down at Station at 5:45. In town. Pegs for a dance.”

September 22, 1918

“Sunday School. Came down with Influenza.”

September 23, 1918

“In bed. Dr. G- came. Mother came home.”

September 24, 1918

“In bed. Felt rotten. School closed till Monday.”

September 25, 1918

“Got up and went out. Felt rotten.”

September 26, 1918

“Hung around. Sick.”

September 27, 1918

“Went over to Pegs”

September 29, 1918

“Church. No Sunday school. Over to Pegs in afternoon.”

October 2, 1918

“Over to Pegs. School still closed.”

Luckily, Barbara survived the influenza epidemic, and it seems the greater impact on her family was that of the school closure.

To learn more about the Influenza Epidemic of 1918, or more about diaries and letters from 1918 please visit the Library at the Massachusetts Historical Society. We welcome your questions and research queries at library@169577.com.

Bibliography:

http://www.massmoments.org/moment-details/flu-epidemic-begins-in-boston.html

http://academic.oup.com/cid/article/47/5/668/296225

http://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-boston.html#

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journal-plague-year-180965222/

http://www.wgbh.org/news/post/1918-influenza-outbreak-when-boston-was-patient-zero

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/influenza-letter/